|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | news | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Unpublished Manuscript #36 |

|||

|

Nine Paragraphs about the Future (in Jacksonville, Florida) |

|||

|

Four Sieges |

|||

|

Agnes and Ned |

|||

|

Jeffrey Brown |

|||

|

Jonny Diamond is a Canadian living in New York City, where he works as

a magazine editor. He still occasionally includes the letter "u" in

colour..

|

|||

|

|

|

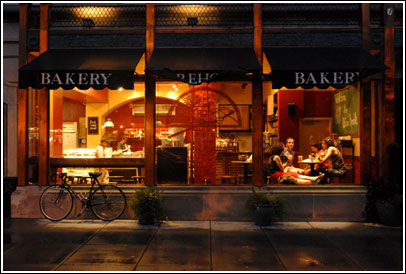

Photo by Sean Carman |

She had death in her hands, in her heart, in the americ tang of her angry sweat: she was jealous of a piece of bread. It was a dark, trunk-thick loaf of Polish bread, and Agnes could think of nothing else. Ned made a special trip to get the loaf, went the long route each week to pick it up at the Polish bakery. Agnes could not remember the last time he'd gone the long route for her. Ned was eleven years older than Agnes, but as they entered their fourth decade together the difference showed less and less. She said nothing to him (it was only a loaf of bread), but she refused to partake. She remained silent as he ate, stared at their commemorative stuffed koala on top of the television, cheap totem of the trip that had almost destroyed them. If Ned noticed her behaviour, he said nothing; perhaps he'd figured out the source of her anger, but it is likely he had not.

* * *

The woman's name was Maria Krakowski. She was in her early forties, had a son of seven. From the very first day, Agnes hadn't liked Maria, hadn't liked the coin-bright tone of her disembodied voice, overheard from the upstairs study of their newly rented house in suburban Adelaide. But she had gotten along with Maria's mother. Despite the elderly Mrs. Krakowski's violent lunges at English idiom, Agnes had made a much-needed friend in a foreign land.

Young Maria was taken with the much older Ned, who for all his years was still talked of by intimates and associates alike as "Ned the Wit" or "Handsome Ned" or "Ned the Tennis Player."

It is not easy for a man of seventy-three to deny the affection of a forty-one-year-old woman. Which is not to say Ned broke his marriage vows (certain things are easier at seventy-three than others), but rather that he explored the fullness of this new friendship to the very limits of propriety.

Agnes hadn't been aware of anything improper -- it was Mrs. Krakowski who'd mentioned it during the intermission of the Walumbalu Players' incomprehensible adaptation-for-stage of The Tax Inspector. Like any good Polish mother, Mrs. Krakowski was a little shamed by her fatherless grandchild (who had a father, biologically speaking, who was somewhere in New Zealand taking core samples) and wanted "no more seelly beezness" for her daughter.

At first Agnes thought Mrs. Krakowski was confused by the play, that her relationship with the English language had finally collapsed. It wasn't until Mrs. Krakowski mentioned a trip to the seaside the two had taken, quoting dates and room service charges for champagne and Tarakihi*, that Agnes saw it: the dull truth of infidelity. The 'truth' at this point was truly dull, having not had the opportunity to become 'sordid', romantic sunsets by the Pacific notwithstanding. But that didn't matter to Agnes; she and Ned had once been in love, more so than anyone she knew of, even in books or poems or films -- and this is what mattered.

* * *

Agnes and Ned had met at a Sunday-afternoon book club in the middle of winter. Ned had just come in from a morning of skiing, his cheeks ruddy from the cold, his eyes particularly blue from the sun (or maybe it was the other way around, recalled Agnes, who was only sure now of the depth of her first impression, if not the details). As Ned would always tell it, he'd actually been looking for a seminar on Equatorial nature photography, but his first glimpse of Agnes -- a thrilling strip of skin and frill exposed through a gap in shirt buttons as she leaned forward in her chair -- was enough to keep him in the wrong room. As everyone turned and noticed the not-insignificant new arrival (to a dwindling group), Agnes sat back and decency was restored to the tableau. They were discussing Lolita, which Ned had not read, and which Agnes was defending to some of the older club members. "Simply because a character in a book is morally problematic, even repugnant, does not make the book inappropriate. It's one thing to argue the success or failure of an author's aesthetic intentions, or his attempts, but to suggest that approval or praise of a book like this is an endorsement of its dubious moral position -- or lack thereof, thank you Stewart -- is ridiculous." Ned's second real look at Agnes took in her slight flush, a by-product of impassioned discourse that he would come to know well: tiny spots of red, the color of Christmas holly, merging into a high blush during both sex and argument, of which their relationship would consist in large amounts.

Agnes' response to Ned's suggestion that they have a cup of coffee was an abrupt "why?" followed by an embarrassed "oh" and a bemused "that would be very nice." From that first coffee -- which became wine, which became breakfast -- they'd never been apart. Theirs was a weeklong fling that had replicated itself over thirty years, adding up to, and here she had to use a napkin for the figures, 1,560 weeks of happiness. Replication: like a genetic anomaly, or some odd kind of cancer, thought Agnes, that instead of tearing things apart, instead of attacking the living cells, made the whole body stronger.

But it wasn't simply the accretion of shared experience that linked them now; nor was it their default victory by attrition against the forces of time. The organism was still replicating, perhaps slowly, perhaps unevenly, but on it went, surviving. But then neither of them had ever been interested in mere survival, thought Agnes, regretting the blunt biology of her metaphor. Survival was for unicellular organisms and civil servants. Damn this infernal dusty country, she thought. Damn it to hell.

Agnes, who'd never been the jealous type, was overcome. No, she thought, this cannot be, I cannot let this be.

Agnes told Ned they had to leave. She told him the continent -- or country or whatever it was -- was driving her mad. The heat, the dust, the gigantic bugs, the bruces and the sheilas -- anything, everything, was awful. She knew there were eight months left on his contract, knew she was pushing him more than she ever had, and knew she could lose him if she pushed too hard. But she knew also that they'd been very much in love once.

Yes they had, thought Ned, who understood this basic truth of his existence without the aid of metaphor or math, and agreed to go home.

* * *

Ned hadn't been aware of a Polish bakery in the adjacent town, but after a brief conversation with the owner, a brick-faced man in a trodden-on T-shirt, he discovered it had been there for twenty years. He lingered in the place, examined carefully the labels in the fridge (all those improbable consonants jammed together), and listened to the brick-faced counterman argue with the hammer-faced baker.

Ned had enjoyed hearing Maria's one-sided phone arguments with her mother, loved the heavy, forced march of Slavic syllables, imagined them as high-cheekboned Eastern hordes pressed together in a valley -- he imagined this and was thrilled by it. He missed the unlikely marriage of Australian and Polish sounds when Maria tried to explain rugby, or when she talked of moving to Sydney. If he thought explicitly of any of this while driving home (a loaf of Polish bread in the passenger seat), he refused to admit it to himself, tried instead to think of women's tennis and warm toast with marmalade.

Ned came home with a loaf of Polish raisin bread, still warm. The man had been very nice, thought Ned, even if his English was occasionally hard to understand. And what delicious bread, why was it he'd not been to the bakery before?

Agnes noticed the new bread immediately.

--What's this bread dear? It looks lovely.

--Oh. It's from a new European bakery at the corner of Blair and Waverly.

Agnes knew of the bakery at Waverly and Blair, knew it wasn't new, and that it was Polish. Unlike Ned, who'd been benignly self-deluding for seventy-three years, Agnes saw the connection between Polish raisin bread and Polish love. It was at this moment that Agnes became a jealous person: the sight of the raisin loaf, smug and warm on the cutting board, filled her with rage. Ned, happily unaware, spread great swaths of butter across the golden face of the bread, bejewelled as it was with succulent, plump raisins.

--Would you like some?

Silence.

--Darling?

--NO.

--All right.

How? she thinks, could he bring this woman into their kitchen? How could he spread butter like that, eat it like that, slowly, obscenely, feeling out each raisin with his tongue? I am not a jealous woman, she thinks, but how can I live with this Polish tramp in my house, on my husband's lips?

* * *

They have travelled three thousand miles to get away from this woman. One of them is an old man who was surprised by love, who misses the sounds of argument on young lips that have spoken his name in adoration. The other is an old lady who has decided to say nothing about the invasion of her kitchen by a memory, because she is not the jealous type. They were very much in love once -- and there between them, still warm from the oven, sits a loaf of Polish bread.