|

|||||||||||||

| archives | submissions | news | (dis)likes | ||||||||||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Overhanded |

|||

|

Lake-Effect Snow |

|||

|

Transit |

|||

|

Proofreader |

|||

|

Ben Greenman |

|||

|

Redefining All-You-Can-Eat: Our 14 Hour Challenge to Ryan's Steakhouse, pt. 3 |

|||

|

Jeff Landon lives in Richmond, Virginia with his wife and two daughters and dog, and he teaches at John Tyler Community College. He has published stories at Quick Fiction, Crazyhorse, Other Voices, Smokelong Quarterly, Wild Strawberries, FRiGG, and Mississippi Review. |

|||

|

|

|

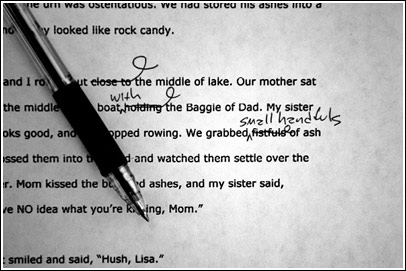

Photo by Sean Carman |

1

My father’s ashes clumped on the way to Smith Mountain Lake—it was probably the humidity. We had transferred his ashes from the urn because my mother thought the urn was ostentatious. We had stored his ashes into a Ziploc bag, and now they looked like rock candy.

My sister and I rowed out to the middle of lake. Our mother sat on the bench in the middle of the boat with the Baggie of Dad. My sister said, OK, this looks good, and we stopped rowing. We grabbed small handfuls of ash and bone and tossed them into the wind and watched them settle like a cloud over the green, oily water. Mom kissed the bunched ashes, and my sister said, “Gross—you have NO idea what you’re kissing, Mom.”

Mom just smiled and said, “Hush, Lisa.”

2

The surgeons sliced open my father’s stomach and said, “Nope, it’s too late, he’s pickled this thing—it’s like a pastrami sandwich in there.”

They zipped him back up and then we all went home to wait it out.

3

“Resentment percolates,” said my father. “My father left us without saying boo about it. I was four years old. Four! I know I’ve made mistakes, Peter, but resentment makes for ugly people, and you weren’t that good-looking to begin with.”

I was driving his car—a 1975 Buick LeSabre convertible--back to his apartment complex. After Mom asked him to move out, my father had joined a group called Swinging Seniors. They met every weekend at the clubhouse at the lake. They were divorced or broken or looking for love. Mostly, they drank cranberry and vodka drinks on the wrap-around deck. The men talked about fishing and the women talked about fishing, too. They were wretched with drink and memory, but here, on this deck, music playing, they held hands and mocked each other’s hats and told huge billowing lies about the fish they’d caught and the lovers who surely still pined for them. In the near dark, they were kindred and soothed by lake water and vodka.

They liked me. I was fifty, the young folks, and they asked me about new trends in music and fashion.

It was summer, and the stars over Smith Mountain Lake tended to blur together and I thought that maybe I was going blind. All around us, the crickets did their thing. I helped my father into the passenger side. We drove for a few miles, no music, no talking.

“Let’s take the top down,” said my father. I pulled over and we dismantled the roof—a complicated, grunting procedure—and then we were on the road again, the wind in our faces and our diminishing hair.

My father raised his arms high over his head and said, “I’m a Jet Plane”

“Dad, stop. You look like a dope.”

4

Ten years ealier, and three years sober, my father signed us up for scuba lessons. Eight weeks and several hundred dollars later, we were certified, and my father paid for our trip to Aruba.

We waddled into the water and fed cheese food to the schools of neon-colored fish that clouded around us. We tapped each other’s tanks they way we were taught to do. We gave each other the OK signal. We established perfect neutral buoyancy, floating in mid-water. We relinquished gravity. I pulled my legs into the lotus position and hovered over my father and the coral that from our distance looked like fire and pumpkins.

5

I met Rene, my future ex-wife, at a country club dance. I was the bartender; she was the rich unhappy girl, tanned under a white dress with spaghetti straps. I was thirty-years-old, a bartender and fry cook.

After the dance, Rene took my hand and we walked out to the golf course.

“Take off your shoes,” Rene said, and I did, and she did, and we stepped onto the putting green on the 14th hole. The grass felt spongy and damp and it seemed to mold around our bare feet. We kissed each other and she put her hands in my hair, the way people do. We weren't kids anymore, but it felt like we were.

6

My last year of high school I took some LSD and lost my mind. It came back, but not before I stabbed my father's tires, all four of them. I walked into his company parking lot, my head crowded with colors and distortions, and stabbed his tires with my pocketknife--a Christmas present from Dad. I walked away and tossed the knife into the Wasena River. I was crying. I couldn't stop. I kept thinking I was going to die. Everything seemed ready to float away, and I grabbed a man's arm, a stranger, to keep him safe and earthbound. He didn't thank me, though.

7

My father was a proofreader.

I was ten-years-old.

Every night, he corrected my homework with a red pencil, and then made me write my final, improved, draft.

One night, bored and angry, I wrote a series of cusswords, in column form: Shit, Fucer, Ass, and Damn. Ten columns of cuss words lined like soldiers.

Ten times, my father circled the word ‘fucer’ and at the bottom of the column he offered the correct spelling, plus a cheery note:

It’s a silent K, Peter. Some words are tricky. Try your best!

Love, Your Father.

8

A photograph: My father stands in the cup of his father’s hands on a beach in Rhode Island in 1943. He’s a baby, a twig. He looks uneasy, the sky behind him, improbably blue. I want to fix this, put in some clouds, a low swarm of seagulls. I want to comb my father's baby hair and tell my grandfather to stop showing off and put that goddamn baby back on the ground, now.